Voices and Monsters

In This Article

-

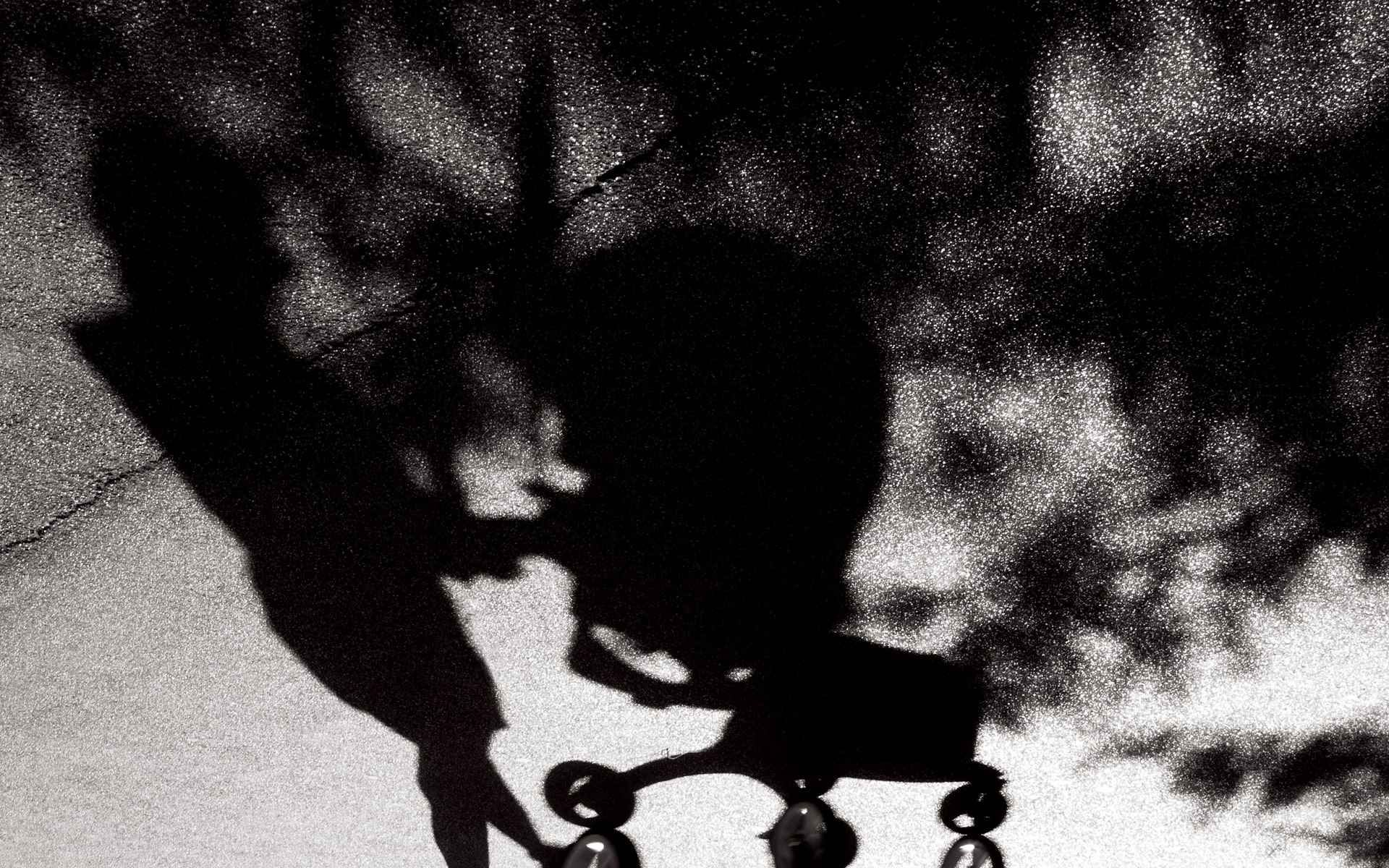

Postpartum psychosis is a rare mental health condition that affects one or two in every 1,000 new mothers.

-

About half of reported cases happen ‘out of the blue,’ to women without previous or familial history of psychiatric illness.

-

Developing symptoms may include a combination of manic or depressive behaviors, such as hearing voices or seeing things that aren’t there, (hallucinations), and believing things that are not based on reality (delusions).

Postpartum psychosis is a rare mental health condition that affects one or two in every 1,000 new mothers. Research suggests it is an overt presentation of bipolar disorder that coincides with hormonal shifts soon after delivery. Onset can be sudden and usually occurs 7-14 days after birth.

‘We can’t keep calling him Baby, can we?’ whispers Davy.

It’s Thursday 29th August 1985, and the cup of tea he brought me is still warm on the bedside table next to an empty plate. I’ve swallowed the last bite of jammy toast and am licking my sticky fingers. I feel loved and lucky, full of everything good, in my nest of pillows cradling the baby in the crook of my left arm. Years later I won’t remember if the morning outside our undergraduate flat in Aberystwyth was bright or overcast because in my low-lit memory the blackout curtains are always drawn, and the bedside lamp always blooms a languid glow.

I match his whisper. ‘Ok, Daddy.’

‘So, we’ll decide tonight then – as his one-week birthday present?’ His words are a distant thrum.

About half of reported cases happen ‘out of the blue,’ to women without previous or familial history of psychiatric illness.

My gaze, like yesterday and the day before draws itself back to the baby. I brush his cheek with the back of my middle finger, watching his eyelids. They’re translucent, like mother-of-pearl, flickering with what I take to be his dreams. My mind is dull with love.

‘Jane, did you hear me?’

I nod without looking up as Davy bends to skim my bedroom hair with his lips.

‘Bye both,’ he says, then kisses his fingertip and touches it onto the baby’s cheek. ‘Don’t forget your bath’s running, Mummy.’

His words seem faraway, quieter than my thoughts and take forever to ripple through the heavy hush.

When the door closes after him I murmur, ‘I won’t,’ then gaze at the baby, watching his white toweling Babygro as it rises and falls. Eventually I haul myself up, sliding my arm out slowly so as not to move him awake then make a barrier of pillows to stop him rolling off the bed.

Symptoms often cascade rapidly and may include sufferers harboring odd beliefs, like their baby has something to do with God, or the Devil.

Next door in the white-wooden bathroom I flick on the lights and turn off the tap. I get undressed and sink into the milky water letting names float around my head, each foretelling a different future. Jimmy will be a writer. Dylan will have his own bakery in the Gothic quarter in Barcelona. Billy will be a scientist who’ll lead the research team who’ll eventually eradicate cancer. I roll the name around my mouth – Billy Bennett-Kermode – imagining my savior baby all grown up, healing the world. It’s a wonderful daydream until an upstart thought cuts through the treacle. How will you leave him when you have to go back to college? The clock is tick-tick-ticking.

The irritating thought has’ been nagging at the back of my mind for days and I’m annoyed with myself for letting it spoil my morning. I get rid of it by standing up and focusing on the here and now. I look through the steam at my hazy reflection in the cabinet mirror, shrimp pink, rippled fat with pendant breasts hanging heavy, full again already, aching fuller still, leaking at the thought of him. I step out and dry myself.

Developing symptoms may include a combination of manic or depressive behaviors, such as hearing voices or seeing things that aren’t there, (hallucinations), and believing things that are not based on reality (delusions).

A loop on the old cotton towel snags on something high up on the back of my leg. I tug it and a thread pulls loose. I’m surprised. There’s nothing sharp about me, not anymore. I run a hand into the puckered arc of my buttock and thigh, feeling for – well, I’m not sure what I’m feeling for – dry skin perhaps or maybe a splinter. My finger recoils, pricked by something sharp. I look to see as a garnet of blood forms cabochon on my fingertip. I lick it away then rifle around in the wicker drawers under the sink to find my compact mirror. I need to see what has made me bleed.

The tiny reflection is difficult to catch, impossible to see in the harsh white light. I twist to get into the right position. It casts no shadow, traps no color, but, narrowing my eyes into slits and poking out my tongue, as though that will help, I just about see it. Growing out of my soft folds, out of my curds-and-whey skin, is a thorn – almost invisible – a sharp, see-through thorn of glass.

‘Get rid of it,’ spits a monster thought.

I do as I’m told, pulling at the thorn, but it’s impossible. It isn’t on the outside stabbing in, it’s on the inside, stabbing out.

‘Snap it off,’ barks the monster thought.

I try really hard, holding my breath, but a fractal of pain, lightening hot, stops me. I try again and again but I can’t, even when I bite my lip hard to trick the pain.

Other symptoms may include panic, confusion and racing thoughts.

I scrabble around in the second drawer down. I might not be able to pull the thorn out but I can make it invisible. Nail-file in hand, I sit on the edge of the bath to reach underneath my leg, feeling my way. I run an exploratory rasp over the point. It’s painless – like filing nails. I file and file, shearing it away into sparkles that fairy-dust the floor. It takes forever and when I’m done, though it isn’t gone completely, it is blunted. I rub oil into the raw skin around it, then all over, to soften myself back to normal, soft enough to hold my baby.

The baby!

I run naked into the bedroom.

He’s sleeping exactly as I left him. The room’s exactly as I left it, burgundy curtains drawn, cup of cold tea on the bedside table. I do what I’ve done so many times over the last few days and sleepless nights, I reach out to touch him, extending my finger to check he’s breathing.

I only see it because the overhead light isn’t on. The lamplight casts a shadow at exactly the right moment just before it connects. In the place where my mother’s touch should be is a talon of glass, almost invisible, poised to slice. I freeze then focus, seeing it clearly now. It’s thicker at the bottom than the top, slightly hooked, tapering to a point. I scream. It wakes him up. He starts to cry.

Common symptoms also include paranoia and feeling useless as a mother.

I want to pick him up to sooth him calm. I need to feed him quiet to release the pressure in my breasts that nursing him would ease.

‘Don’t touch him,’ spits a monster thought, ‘you’ll hurt him, with your thorns of glass.’ So instead, I look down at his jerky kicks and desperate fists as he cries himself crimson.

‘Thorns lead to more thorns,’ growls the monster thought.

I turn my hands over, and sure enough, another crystal pin-prick is almost breaking the surface of my right palm.

‘There might be one on your breast.’ The monster thought whispers my darkest fears like they’re delicious. ‘There might be one on your nipple.’

I blink away the image that springs into my mind, my insides shriveling to nothing. The baby turns his head sideways, rooting, frantic to latch on. I hold him away from me, folding the thorn into my palm, feeling with my safe middle finger. The nipple is safe. I sigh with relief as his hard gums clamp down and we connect, then I sit rigid against the wooden headboard too afraid to move myself comfortable, trapped and stiff with a growing thirst. By the time he’s finished and sleeping safely away from me in his cot, we’ve worked out a plan, my monster and I.

‘No-one must know,’ it said, and because I was afraid, I agreed.

‘Especially Davy, he mustn’t ever know. I’m here now to help you cope, and if no-one sees them, if he doesn’t see them, no-one will ever know how dangerously, cruelly, terribly sharp you are.’

Typically, it is a family member, often the partner, who realizes something is wrong.

It’s a week later though I don’t know it. I’m scrubbing hard, sterilizing dozens of new bottles in my yellow kitchen gloves, screwing the brush round and round as hard as I can, to scour the tainted plastic.

‘Bye then,’ says Davy from behind my back. I feel him hovering, wanting to kiss me goodbye.

‘See you at teatime,’ I say in monotone, screwing harder to avoid the kiss.

‘Let him go,’ yawns the monster. ‘It’s not like you can let him anywhere near you, is it? Not with those disgusting thorns.’

‘S’pose not,’ I reply, forgetting myself, too tired to argue.

‘Did you say something?’ says Davy.

I turn and look at him like he’s mad. He makes his face expressionless to hide what he’s really thinking, then walks over to the pastel carrycot, kisses his finger and smears the dirty kiss onto Billy’s sleeping cheek.

‘Do you have to,’ I say. ‘It’s full of germs.’

‘Bye,’ he says again, hesitating at the door.

I sit down at the table seeing it all from far, far away.

‘You’d better get a-filing,’ sing-songs the monster, ‘so they’re nice and short and safe and secret.’

It is rare for mothers with postpartum psychosis to harm their babies, but the cognitive disorganization associated with the condition, often results in them being neglectful of their baby’s needs or harming themselves.

There’s a noisy silence echoing through the kitchen in the wake of the slap. Billy is wet-faced, sitting in his bouncy chair. He’s just stopped crying and is breathing-in in shocked, jerky sobs. I can hear him but not feel him. I turn and stare at the naked hands in the washing-up bowl.

Billy was crying and I was so tired, so exhausted that I hadn’t been keeping on top of things, letting myself go, letting my secrets show. An unfiled thorn had pierced the marigold latex. It had let the dirty water in. I’d snapped the gloves off and hurled them wet against the wall, screaming wild and high like the banshee I am. They’d slapped hard, trailing a watery bruise down the magnolia paint.

‘Chop it off,’ snarls the monster. ‘Chop it off – the whole bloody hand. Chop off the whole bloody useless thing,’ and I watch as it claps its leathery hands, dances on its filthy feet, its glassy talons click-tapping on the Lino, so I don’t hear Davy behind me, home early because he’s worried sick and we really have to talk. I don’t hear him reaching out to touch my shoulder.

I swing round raising my hands to slash. He takes them in his, turning them over slowly. Time stops as he kisses my sharpest point, pressing his lip to its pin-prick tip. I try to pull away and am surprised when it draws no blood. That night, whilst Billy sleeps, I let him talk to my monster, and show him all my thorns.

Current recommended treatment includes admission to specialist mother and baby units, where talking treatments and antipsychotic medication including mood stabilizers can be administered without separating mother and child.

Billy and I came home six weeks later. Not from hospital, but from Blackburn in Lancashire where my stepmother was sister on the Intensive Care Unit. She used her contacts to access outpatient treatment for me and I received better care than most could expect in 1985. Then, postpartum psychosis was still medically undescribed and there were no generally agreed symptoms or treatment plans. Writing this is the first time I’ve set my experience into the context of current understanding and I’ve been struck by what a textbook case I was. It feels empowering, normalizing, therapeutic even, and makes me appreciate how fortunate I was, getting the treatment I did. Especially so, because sadly, my treatment was good even by modern standards. Though postpartum psychosis is better understood nowadays, beds in mother and baby clinics are still few and far between and there are huge regional differences that make service provision patchy. Diagnosis is often missed or comes too late, all of which seems properly crazy because it’s such a treatable condition, a very temporary madness. Without treatment, it can last for years, interfering with a mother’s ability to connect with and care for her children, causing incalculable long-term harm to mother and child.

And then there’s the prejudice and stigma. The stigma attached to having had postnatal psychosis is as real now as it was in 1985. It makes people hide that they’ve had it, so they never talk about coming out the other side of the strange and scary rabbit hole, and never share their stories. That’s why I’m writing this, though it’s taken me thirty-two years to pluck up the courage.

That first evening back in Aber, I was feeling how lucky I’d been even without the benefit of hindsight. Everyone had finally left us in peace and I was skim-reading The Guardian at the kitchen table – pit closures in Yorkshire, the Broadwater Farm riots – not exactly uplifting, but it still felt good to be back in the real world.

Davy had brewed up and was balancing toward me carrying two teacups that rattled fragile on their bony saucers. Funny what sticks in your memory – he looked like he was tightrope walking. I put a careful finger through the handle and raised my cup, miming a toast so as not to risk the brittle china, then took the small white neuroleptic from the saucer and swallowed it with the first sip.

‘Welcome home, Mummy,’ he said.

The scars where the thorns still scratched just below the surface were almost invisible that night, not in a whimsical, happily-ever-after kind of way, but really, because they’d started to become ordinary – part of our everyday landscape – and because my monster was sleeping, sleeping like a baby.

References List

- National Childbirth Trust (n.d.) What is Postpartum Psychosis? [On-line]. Available at https://www.nct.org.uk/parenting/what-postpartum-psychosis (Accessed 28 Feb 2020).

- National Health Service (2014) Postpartum Psychosis [On-line]. Available at http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/postpartum-psychosis/Pages/Introduction.aspx (Accessed 28 February 2020).

- Postpartum Support International (n.d.) Postpartum Psychosis [On-line]. Available at http://www.postpartum.net/learn-more/postpartum-psychosis/ (Accessed 28 February 2020).

- Royal College of Psychiatrists (2014) Postpartum Psychosis: Severe mental illness after childbirth [On-line]. Available at http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/healthadvice/problemsdisorders/postpartumpsychosis.aspx (Accessed 28 February 2020).

- Sit, D. Rothschild, A.J. Wisner, K.L. (2006) A Review of Postpartum Psychosis [On-line]. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3109493/ (Accessed 28 February 2020).

- Wikipedia (2016) Postpartum psychosis [Online]. 26 October 2016 Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Postpartum_psychosis (Accessed 28 February 2020)